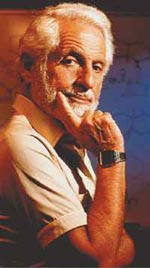

Shebang:

There must have been a moment; we aren't talking about a Eureka moment

but an enormous satisfaction

Djerassi:Of course, there is satisfaction, but it took some time

to appreciate what we had done.. Remember, as chemists we had a rationale

that this particular chemical ought to have progestational activity and

hopefully ought to be orally active. So we then sent it to a commercial

biology laboratory which was associated with the University of Wisconsin

because we were just a chemical operation in Mexico, we did not have a

biology laboratory. . They tested it for progestational activity in the

conventional animal at that time, rabbits. Well, lo and behold, they let

us know that this new steroid of ours was eight times as active as progesterone.

Now that was fantastic already. Because literally it meant that first

of all we had made now the most active progestational compound known in

- you know - in history, you could say.

Eureka!

Secondly, more exciting, it turned out that it was orally active. So that

was the Eureka part. To get confirmation from the biologists that what

we had was right what we had dreamed about. That if you make these

particular chemical changes in the steroid molecule and make a the new

one, it would be orally active and we had anwith the additional bonus

it would of being even more active than progesterone.

Pincus

Now the moment that happened then of course it was sent to all kinds of

different people, including to Gregory Pincus who was a biologist

at the Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts.

2000 miles away from where we were. He was a very well-known biologist

who was already at that time interested in the ovulation inhibitatory

properties of progesterone, and therefore he was very much involved with

the contraceptive aspects rather than the other, the therapeutic aspects

of it. Gregory Pincus was the one who is generally - and it's perfectly

appropriate -considered the Father of the Pill - if you permit us chemists

to be called the -

Shebang: Mothers.

Djerassi: Mothers. He and his team developed it biologically.

In those days this involved tests with rabbits and so on. And then the

midwife was John Rock, [a Catholic who was pro-birth control]

. He was a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Harvard Medical

School in Boston, and he did the first clinical experiments. He would

appropriately be considered by my metaphor to be the midwife. Now the

Eureka moment came with the validation of the hypothesis that we had been

able to synthesize an orally active steroid that retained the biological

activity of progesterone. We learned that we had achieved that within

5 or 6 weeks of our synthesis, around November 1951...

Shebang: What do you do then when you have a moment

like that, when you learn that you've succeeded like that? Do you shout,

yell 'Yes, yes, yes!'? What do you do?

Djerassi: Mmm - it is like almost all-successful research it is

very orgasmic - in many senses! It is an unbelievable high, but for a

very short space of time! [LAUGHTER]

Because, because the reality sets in. I mean you want to do it all again.

Frequently [LAUGHTER] and you can't just repeat that.

And secondly, you discover that there are going to be some problems, along

with the joy. To carry on with the sexual metaphor: My God did I get the

woman pregnant?

Shebang: What are the consequences?

Djerassi: What are the consequences? These really sink in only

after a while. Because to a chemist, again, the initial question would

be: So far, I only managed to make a few milligrams. But the question

arises, how do I make grams, how do I make kilograms and so on. And technically

this was a very complex problem. A very complex synthesis was required

considering the kind of chemistry that was done then. It was tough chemistry.

It still is.

And so I think we can pat ourselves on the back And we did get an awful

lot of recognition for it.

I'm talking about scientific recognition, the recognition that really

counts for a scientist.

Interestingly enough, there is something in the States called the National

Inventors' Hall of Fame. The very first invention of a drug they entered

there was our patent. We were put in there at the same time as Edison's

invention of electric light. The very first medical one was our patent

of the Pill.

And to give you another illustration: Recently, during the millennium

hoopla, the London Times had something on the thirty most important individuals

of the millennium. It starts with Newton and so on.

[Carl Djerassi is listed by the London Times as being

the 30th most important person of the millennium]

Shebang: Wow!

Djerassi:I am really the only living person in this list. But of

course in many respects it is totally ludicrous to have me there. You

don't have Mozart there. They have Shakespeare and -

Shebang: Luther, Copernicus, Magellan, you are

on this list with -

Djerassi: Einstein, Lenin

Shebang: Einstein, Lenin - [LAUGHTER]

Shebang: Pasteur, Darwin, Bonaparte...

Djerassi: But you see, the important point - this is what I want

to draw your attention to - you really have to divide these 30 people

by fields. It's ludicrous to put me into this group. In a certain sense,

it's even inappropriate to put Newton in there. About 15 of the 30 happen

to be scientists. And for the London Times who drew this up, numero uno

was Newton. But in a way, you see, if Newton had not been there, if he

had never lived, the laws of gravity and motion, the Principia would still

have been done, 1 year later, 5 years later, 20 years later. If Einstein

had not lived, someone else would have come up with Relativity. If Max

Planck had never lived you still would have had the quantum theory, no

question whatsoever, quantum mechanics and so on.

And if I had never lived, the oral contraceptive would have been developed

in a few months, a few years later. Because the fact is that the time

was right.

Art and Science

On the other hand, King Lear could never have been written. No-one other

than Shakespeare could have written Lear, no-one other than Dante could

have given the world the Divine Comedy. So having Shakespeare and Dante

on this list is of course correct because they really are amongst the

giants of the millennium. In a sense scientists are surrogates and it

is well worth the effort to help people to recognize this.

Shebang: In a previous issue of Shebang we have

an interview - [see Archives] - in which Lewis Wolpert says exactly the

same thing. You rerun history, the scientific discoveries would all be

made in due course, the chronology might be different, but the discoveries

would be made

Djerassi: Yes.

Shebang: You rerun the history of art, who knows

what would happen.

Djerassi: Absolutely.

Shebang: Next. Next. The National Medal of Technology

in 1991 for 'promoting new approaches to insect control'. So here you

are in another area.

Djerassi: Yes.

Shebang: Another world problem.

Djerassi: Another world problem. But here the Eureka concept is

more appropriate, and yet it's interesting that this work on insects was

very much primed by my early work on oral contraceptives.